Understanding Betrayal Blindness

Betrayal blindness is a survival response where someone unconsciously ignores, minimizes, or forgets abuse or betrayal—often by a trusted person—in order to maintain the relationship or access to safety, resources, or belonging. It can show up as denial, confusion, or memory gaps around harmful events. This defense protects the individual in the short term but can create long-term difficulties in trust, self-perception, and healing.

Introduction to Betrayal Blindness

Betrayal blindness is a psychological phenomenon where individuals remain unaware of betrayal, especially in close relationships. This concept, first introduced by Dr. Jennifer Freyd, helps explain why victims of abuse, particularly narcissistic abuse, might not recognize or acknowledge the betrayal they face. The intricacies of this phenomenon are deeply rooted in human psychology and survival instincts.

Studies on Betrayal Blindness

Research has shown that betrayal blindness is a coping mechanism that helps individuals maintain necessary relationships.

One study found that victims often remain oblivious to the betrayal to preserve a sense of safety and stability. For example, children who depend on their caregivers for survival may unconsciously ignore abusive behaviors to ensure their needs are met.

Similarly, adults in abusive relationships might exhibit betrayal blindness to avoid the emotional turmoil and practical difficulties of confronting the abuse.

Another significant study highlighted that betrayal blindness is not just a passive process but an active psychological strategy. The brain can suppress memories and emotions related to betrayal to protect the individual from potential harm. This suppression helps the victim maintain a sense of normalcy and reduces the cognitive dissonance that arises when a trusted person betrays them.

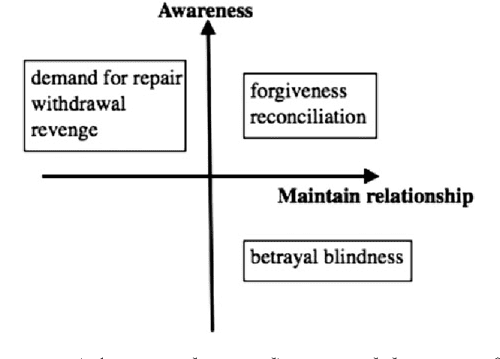

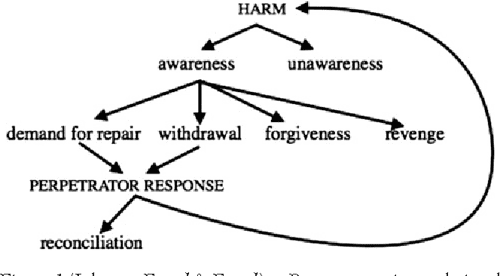

If a victim is aware of the harm, he or she then has the choice to demand repair, withdraw from the relationship, forgive the perpetrator, or enact revenge (see image above). After a demand for repair or withdrawal, the victim’s next options depend on the perpetrator’s response.

If the response is a good one, reconciliation might occur, whereas if the response is negative, it constitutes a new harm and the suite of behavioral options re-starts.

Importantly, the option of awareness depends upon the victim’s degree of empowerment in the interpersonal relationship in which the harm occurred.

As the target article notes, a victim’s response depends heavily on his/her relationship with the perpetrator. For example, McCullogh et al. predict that relationships with expected future value are more likely to be forgiving.

However, categories of interpersonal relationships involve more than just their perceived future value.

Dependence is a particularly important dimension of relationships. Being dependent on others for material and emotional support has profound implications for adaptive responses to harm.

Betrayal Trauma Theory (Freyd 1996; DePrince et al.2012) posits that when a victim is significantly dependent on the perpetrator, it may be adaptive to remain unaware of the harm the perpetrator imposed. A dependent victim is essentially required to maintain the relationship with their aggressor.

Most of the options shown at the top of the page in which follow awareness may be detrimental to the relationship on which the victim depends and therefore are not adaptive.

Examples of Betrayal Blindness

Ignored Infidelity: A spouse may overlook multiple instances of infidelity by their partner, rationalizing or excusing the behavior despite clear evidence.

Business Partner Deception: A business owner may continue to trust and invest in a partner who has embezzled funds, dismissing warning signs or suspicions.

Parental Betrayal: A child may continue to idealize and defend a parent who has consistently neglected their emotional needs or even abused them.

Friendship Betrayal: A person may remain close to a friend who has repeatedly betrayed their trust, such as spreading rumors or sharing confidential information.

Professional Betrayal: An employee might continue to support a supervisor who takes credit for their work, overlooking the lack of recognition and fairness.

Political Betrayal: A supporter of a political figure may overlook or downplay evidence of corruption or unethical behavior because of strong ideological alignment.

In each case, betrayal blindness manifests when the betrayed individual ignores or minimizes the betrayal due to factors such as emotional attachment, fear of facing the truth, or a desire to maintain the relationship or status quo.

Inquiry and Transcendence

Dr. Michelle Mays, the founder and Clinical Director of the Center for Relational Recovery and author of The Betrayal Bind: How to Heal When the Person You Love the Most Hurt You the Worst, asserts that overcoming betrayal blindness is achievable but demands several key elements:

Establishing a secure and supportive relationship.

Showing readiness to confront injustice and betrayal.

Embracing one's personal truth.

Being prepared to distance oneself from relationships that may superficially seem adequate but are genuinely toxic.

In her approach to treating betrayal blindness, Dr. Mays focuses on raising awareness of these behavioral patterns. To facilitate this process, she encourages her clients to consider the following questions:

What emotions would I need to confront if I addressed this issue?

What aspects of this situation frighten me?

What might I risk losing?

What kind of support do I require to confront and acknowledge the reality of my circumstances?

How can I cultivate the strength and stability needed to confront the issues I have been avoiding?

The Importance of Awareness

Understanding betrayal blindness is crucial for both victims and those supporting them.

Recognizing this phenomenon can help victims come to terms with their experiences and seek the help they need. It also underscores the importance of creating a supportive environment where victims feel safe to acknowledge and address the betrayal they have faced.

By raising awareness about betrayal blindness, we can better support those affected by abuse and other forms of betrayal, ultimately fostering healing and recovery.

Betrayal Blindness in Narcissistic (Antagonistic) Abuse

Narcissistic abuse—more broadly understood as a form of antagonistic abuse—involves sustained patterns of psychological manipulation, coercive control, and relational harm.

While it is often associated with Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), antagonistic abuse can be carried out by individuals with or without a clinical diagnosis. It's also important to note that NPD as a diagnosis tends to act as a junk drawer to describe abusive people; in reality it's just as likely for an abuser to have another diagnosis, such as ASPD--or even to have no diagnosis at all.

The core issue is not the diagnosis itself, but the persistent use of interpersonal strategies that seek dominance, control, and psychological destabilization.

In these dynamics, betrayal blindness often becomes a vital survival strategy. Victims may unconsciously suppress or distort their awareness of the abuse because acknowledging it would threaten the emotional, physical, or financial security provided by the relationship.

This is particularly true when the abuser is a romantic partner, caregiver, employer, or authority figure—someone the victim relies on or idealizes. Common tactics in antagonistic abuse include gaslighting, emotional withholding, blame-shifting, and intermittent reinforcement, all of which undermine the victim’s ability to trust their own perception and intuition.

Adding to the complexity, betrayal blindness in antagonistic abuse is often compounded by social stigma and internalized shame. Victims may fear being seen as weak, complicit, or naive. Naming the abuse can feel like admitting failure—not only in judgment but in character. To maintain a sense of coherence, self-worth, or loyalty, the victim may stay silent, minimize harm, or reinterpret harmful behavior as acceptable, necessary, or deserved.

Again, the term “narcissistic abuse” has become highly diluted in popular culture, often used as a catch-all phrase for unpleasant or emotionally immature behavior; there is growing concern among clinicians and survivors about the dangers of “armchair diagnosing." Labeling someone a narcissist because they exhibit “toxic” traits. Traits like defensiveness, selfishness, or emotional unavailability exist on a spectrum and are not exclusive to personality disorders.

When laypeople (or even clinicians without proper training in diagnosis of personality disorders) pathologize these traits as NPD without proper clinical context, two forms of harm occur:

It undermines the seriousness of true antagonistic abuse, making it harder for survivors to name their experience or be taken seriously when they do.

It further stigmatizes individuals who genuinely live with NPD, a disorder that is often rooted in profound early trauma, shame, and emotional fragmentation.

Not every harmful relationship dynamic is rooted in narcissistic abuse, and not every difficult person is a narcissist. Moreover, not all survivors need to know whether their abuser meets criteria for a personality disorder—what matters is the pattern of relational harm, the impact, and the path toward healing.

Citations:

Deprince, Anne P. et al. “Motivated forgetting and misremembering: perspectives from betrayal trauma theory.” Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation 58 (2012): 193-242 .

Johnson-Freyd, Sasha and Jennifer J. Freyd. “Revenge and forgiveness or betrayal blindness?” The Behavioral and brain sciences 36 1 (2013): 23-4 . [see images at the top of the page).